This website uses cookies to improve your experience. We'll assume you're ok with this, but you can opt-out if you wish. Read More

The Next Round: What happens after you change your drinking?

Novelist and songwriter Louisa Young has written this week’s guest blog for us, based on her best-selling book of the same name. Here Louisa tells us her experience as someone who loved someone who drank too much alcohol. Here’s a glimpse into her heartbreaking love story.

We all knew that you drank twice your share in half the time…

I always knew my boyfriend drank too much. But loads of people drink too much. And when you’re young, you don’t know how it’s going to end up. Here’s a useful way of looking at it: it’s not what you drink, or how much; it’s why you drink, and what it does to you.

Robert and I had a thing for each other since we were 17. A 25-year friendship/romance followed before we finally got together for good. His drinking brought us together initially, in the usual social way — by relaxing us. But it also kept us apart — because it was too much, it scared me. Yes he was charismatic, handsome, talented, hardworking, kind and witty, but he was also a depressive argumentative chain-smoking drunk. His drink problem snuck up, over the years. He was a musician and TV/Film composer, and that world was full of booze. I recall him saying, aged around 30: ‘I don’t have a problem with drink. I haven’t had a drink for three days. Except beer. There’s a bottle in the fridge and I haven’t even thought about it.’ And I thought, ‘That’s not what someone who doesn’t have a drink problem says.’

Alcoholic excess seems so normal in Britain that at first you don’t notice. But over time it becomes clear. Things that were funny started to edge in to being dangerous. He’d never go to bed. He’d climb things, stupidly, on a dare. He lost his sense of proportion. He’d argue with friends and sometimes pick fights with strangers until someone hit him. He married swiftly, and the marriage swiftly fell apart. And I grew fearful, both for him and of him.

We were 42 when I told Robert straight that he had to stop drinking.

‘Why does everybody say that?’ he said, crossly.

‘Because it’s true,’ I replied.

Denial is the first symptom of addiction, and the first person alcoholics lie to is themself.

So I want to write now from the point of view of the people who love someone who is alcoholic. People often say ‘Oh why don’t you leave them?’ Sometimes leaving them is the best thing to do, but it’s not always that simple. Sometimes, the reason is, we love them. We know that being alcoholic is only one thing about a person, that we still love that person, and that we want them back, sober. We love them and we hate the alcoholism that poisons what we love about them.

Loving an alcoholic, we don’t know who we’re living with. They’re not even here – physically, because they’re off drinking and emotionally they’re absent because they’re drunk. When they come back, we don’t know if we’re going to get the lovely person we love, apologetic with a bunch of flowers and a hangdog expression, or the aggressive, sarcastic, defensive, person who has temporarily taken them over.

We doubt our judgment. We don’t want them to be drinking; they say they’re not and we want to believe them — but of course they’re lying. Repeated contradictions make us think we’re going mad. We want, desperately, to help. We love them! But if we try to talk to them, we are a nag and a bore who’d drive anyone to drink. If we try to take alcohol away from them, they snap at us. Most of all, if we do help them, we are punished because to be honest we’re just making the whole thing last longer, and the next thing we know we are being called ‘co-dependent’, and ‘enabling’. And they’re still drinking.

It’s hard to accept that we are part of the problem we hate so much; we get embarrassed and ashamed. So we struggle along in silence not wanting to be disloyal to the person we love, or to let those closest to us see our pain.

We don’t want to let anyone down.

Inside, we wonder if it is our fault somehow, but addiction is nobody’s fault — addiction is partly genetic, partly psychological and partly circumstantial. But it is somebody’s responsibility — not ours. Theirs. Addicts, just like anybody, have choices.

Fault and responsibility are not the same thing. Say you have a puppy, and it does a mess on your neighbour’s doorstep. It’s not your fault, but it is your responsibility. So you clear it up. The alcoholic, though, is not a puppy. They’re a human. If they crash the car, it’s not our responsibility to sort it out. Doing so infantilises them — they’ll never have to acknowledge the damage they’re causing. They won’t even see it, because we have so kindly dealt with it. So how can they take responsibility? ‘This is me!’ they say. ‘I am who I am. I know what I’m doing, I’m not like that stupid alcoholic over there.’ And that would be so nice, if it were true. But that alcoholic over there was saying exactly the same things a few years ago, even as their behaviour made their family hate them, and they developed the liver disease or heart condition, the nerve or brain damage, the throat or stomach cancer, that killed them.

Finally, aged 42, Robert admitted he had a problem, and he wanted to stop. He was exhausted and hit, many times, what AA call Rock Bottom. He realised he couldn’t keep going like this. Once it was acknowledged, he was able to look with clear eyes at what drinking was doing to him, and admit that he needed help. On that promise, we finally got together as a proper couple. It took him five extreme years, in and out of recovery centres and rehab, misery and depression, epilepsy and psychosis, lapse and relapse but he did it. Rock Bottoms during these five years included breaking his foot so badly one frozen night it was hanging by the flesh, brain damage, and a coma the medics said he would never come out of. But he got there.

He had been two and a half years sober with AA, relieved and really working at rebuilding, when he was diagnosed with throat cancer. A week before his surgery he proposed to me. He stayed sober through the illness, the surgery, the loss of speech and the ability to eat, the chemo. And he told me that he’d rather go through cancer again, and the ferocious treatment it entailed, than be an active drinking alcoholic again. Because with cancer the enemy is clear; with addiction the enemy is you.

There was no cancer in him, and no alcohol in his bloodstream when, two years later, he died. I can’t write again about how it happened. It’s nearly seven years ago now but it still makes me weak to think about it.

The Sunday after Robert died, I went, nervous, shaky, and alone, to his regular AA meeting. Two people there spoke about doubts they were having, saying that the people around them weren’t being supportive, they were bored with their problems, that they didn’t know why they bothered coming to meetings, that nobody cared. At the end I was allowed to speak. Rather incoherently, I told them of Robert’s death, and said that even if they didn’t feel great about their own recovery today they had helped in his. Even though he had died. I told them how much what they did had helped me, and Robert’s son, even though they didn’t know we existed. I told them that there were thousands — millions? — of us at home, who they probably never thought of, but who valued AA hugely, that their contribution was priceless, because it supported not just the people in the meeting, but us at home as well, and I thanked them. And I thank all of you too, who are dealing with your problem, who are reading this today.

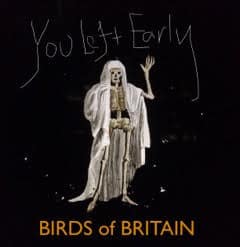

The voice of the people at home isn’t heard that often — which is why I’ve written an exceptionally personal book about all this, and thrown it out into the world. It’s called You Left Early: A True Story of Love and Alcohol, and it came out this summer. Since then I’ve been up and down the country talking about it, and meeting people in similar situations to mine. It’s touched hearts and it’s touched a nerve. And, I’ve made and released an album of my own exceptionally honest songs — also called You Left Early — my debut album! Both book and album chronicle of what I went through being with Robert. I write about the state of the flat Robert wouldn’t let me go to, because in it he drank to oblivion and pissed in his empty vodka bottles. About the neighbour who took him out into the street because you can’t be sectioned on private property. About how when your true love has cancer you’re an angel of mercy; but when he’s an alcoholic you’re a fool not to leave him, even if he’s been your friend since you were 17. About chemo, and life-support machines. About losing the love of your life over and over again, and getting him back, and then finally losing him forever — because of alcohol.

Yes, it’s embarrassing, painful, private stuff. But there are a million and a half people in the UK who are alcoholics, many with people who love them wishing to God that they weren’t. There’s no point writing about it if I’m not going to be honest. I’d like us all stop feeling ashamed about alcoholism, and to treat it as the disease it is. As a widow to that disease, I’d like us to admit how widespread it is. To help each other, openly.

Fifty years ago, people didn’t used to talk about cancer. Now, we do Marathons in pink animal onesies to raise money for research. Can we please open our hearts, save our lives, and talk about alcoholism now? We need to fling up some windows, shine some light, and start this conversation out in the open. This is my way of doing that.

You Left Early; A True Story of Love and Alcohol (Borough Press) £14.99

You Left Early by Birds of Britain, on Download, CD, and Vinyl, from 79p-£17.99

This website uses cookies to improve your experience. We'll assume you're ok with this, but you can opt-out if you wish. Read More

| Name | Domain | Purpose | Expiry | Type |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| wpl_user_preference | joinclubsoda.com | WP GDPR Cookie Consent Preferences. | 1 year | HTTP |

| PHPSESSID | www.tickettailor.com | PHP generic session cookie. | 55 years | HTTP |

| AWSALB | www.tickettailor.com | Amazon Web Services Load Balancer cookie. | 7 days | HTTP |

| YSC | youtube.com | YouTube session cookie. | 55 years | HTTP |

| Name | Domain | Purpose | Expiry | Type |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| VISITOR_INFO1_LIVE | youtube.com | YouTube cookie. | 6 months | HTTP |

| Name | Domain | Purpose | Expiry | Type |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| _ga | joinclubsoda.com | Google Universal Analytics long-time unique user tracking identifier. | 2 years | HTTP |

| sbjs_migrations | joinclubsoda.com | Sourcebuster tracking cookie | 55 years | HTTP |

| sbjs_current_add | joinclubsoda.com | Sourcebuster tracking cookie | 55 years | HTTP |

| sbjs_first_add | joinclubsoda.com | Sourcebuster tracking cookie | 55 years | HTTP |

| sbjs_current | joinclubsoda.com | Sourcebuster tracking cookie | 55 years | HTTP |

| sbjs_first | joinclubsoda.com | Sourcebuster tracking cookie | 55 years | HTTP |

| sbjs_udata | joinclubsoda.com | Sourcebuster tracking cookie | 55 years | HTTP |

| sbjs_session | joinclubsoda.com | SourceBuster Tracking session | Session | HTTP |

| Name | Domain | Purpose | Expiry | Type |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| mailchimp_landing_site | joinclubsoda.com | Mailchimp functional cookie | 28 days | HTTP |

| __cf_bm | tickettailor.com | Generic CloudFlare functional cookie. | Session | HTTP |

| NID | google.com | Google unique id for preferences. | 6 months | HTTP |

| Name | Domain | Purpose | Expiry | Type |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| _ga_10XZMT03ZM | joinclubsoda.com | --- | 2 years | --- |

| AWSALBCORS | www.tickettailor.com | --- | 7 days | --- |

| cf_clearance | tickettailor.com | --- | 1 year | --- |

| VISITOR_PRIVACY_METADATA | youtube.com | --- | 6 months | --- |

Join Club Soda for 10% off your first order of drinks for UK delivery. Plus get our latest news and special offers for members to choose better drinks, change your drinking and connect with others.

If you get an error message with this form, you can also sign up at eepurl.com/dl5hPn